Land Cooperatives vs. The Farmland Commons

Two different but complementary collective land ownership models.

Narration by Kristina Villa

There is a palpable sentiment growing among citizens of the United States that our housing and real estate markets are out of control. We are facing an unprecedented national housing crisis while simultaneously losing precious working farms every day to development and industry due to rising farmland prices that wildly exceed the means of the vast majority of farmers.

Many of these farms have been productive for generations, yielding a resilience woven deep into the fabric of a family and community. But what happens when the relentless tide of capitalism threatens to sever that beneficial connection? What becomes of the collective wisdom and vitality gleaned from seasons of tending the soil together?

This isn’t just about land and it’s about belonging. It’s about the living threads that connect us to a regenerative landscape and to each other. In a world increasingly defined by extraction, exploitation, and the cold calculus of the transactional real estate market, a different way is rising: the shared resilience of land cooperatives and the Farmland Commons. These aren’t relics of a bygone era, but vital, breathing alternatives that dare to ask: is land more than just a commodity? Can it be a shared inheritance, a foundation for collective and ecological flourishing?

At their core, Land Cooperatives and the Farmland Commons are collective ownership structures that address a major issue in our modern-day world: land has become unaffordable.

Below, we would like to highlight the benefits of these powerful models, exploring their promise in a world desperately seeking strength in community and a more just relationship with the earth that sustains us all.

Shared Land Ownership

At their core, Land Cooperatives and the Farmland Commons are collective ownership structures that address a major issue in our modern-day world: land has become unaffordable. It is so expensive that it is nearly impossible for the next generation of farmers to take over where elder farmers have left off.

Access to farmland is the biggest barrier to new and beginning farmer success, and the rising costs have all but halted the transition of farmland from one generation of land stewards to the next. Elder farmers are forced to sell their farmland into the market in the hopes of providing for their retirement. This leads to working farms with dialed-in systems, infrastructure, and productive soils getting dismantled into pieces. Those with commoditized value are sold and those without are discarded. Meanwhile, young farmers are forced to buy or lease raw land and start from scratch, because it is what they can afford.

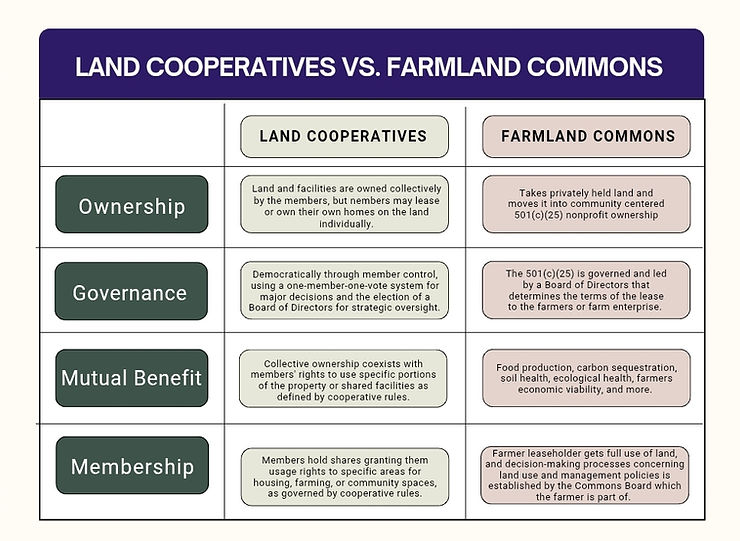

Both Land Cooperatives and the Farmland Commons bring land into a form of shared community ownership. This immediately makes land accessible and protects vulnerable land from development by spreading the financial burden and responsibilities. Land Cooperatives are based on shared private ownership of the land by a democratically run organization of individuals, while the Farmland Commons model holds land in public ownership as a nonprofit. The two models are quite different but can be complementary. In today’s realities, we see cooperatives and commons models as desperately needed.

Cooperatives vs. The Commons

Serving their members and community through diverse means, both organizational types can share complementary values, and both may choose to focus solely on farmland, farmers, and food production.

Land Cooperatives

Rooted in democratic governance and mutual benefit, cooperative models provide a unique structure for individuals and businesses to collaborate on shared goals. Land Cooperatives may hold nonprofit status somewhere in their structure but are predominantly formed into a corporation with members who are shareholders. In contrast to traditional corporations, cooperatives emphasize equitable participation and resource sharing, promoting a more sustainable and community-focused path to property use and development.

cooperatives enhance needed services, strengthen local economies, and address social and community needs effectively.

- Ownership

The land in a Land Cooperative is owned collectively by the members, rather than by individuals in a fee-simple arrangement. This can look different depending on the bylaws written by each cooperative. Members own the land and facilities collectively but may lease or own homes on the land individually. Members, also known as shareholders in the corporation, can sell or transfer their membership to someone else who would take over their required contributions, financial and otherwise, and enjoy the shareholder benefits. The corporation formed as the community’s legal entity holds title to the entire property and assumes responsibility for the mortgage, taxes, and other legal obligations necessary for ownership and operation.

- Governance

Land cooperatives are governed democratically through member control, typically using a one-member-one-vote system for major decisions and a board of directors election for strategic oversight. Operational policies and bylaws are member established and amendable, while member-comprised committees often advise on specific areas, ensuring broad participation, accountability, and mutual benefit. Decision-making can range from direct membership votes to representative votes via the board, with multi-stakeholder cooperatives (including those with on-site farmers, consumers, and community members enmeshed) often having bylaw provisions to balance diverse interests in governance, ensuring equity.

Rooted in a shared community vision or purpose, land cooperatives elect the board of directors to ensure the community stays true to its mission. Sometimes, staff may be hired within the community to manage daily operations. Member participation in decision-making, committees, and adherence to bylaws and land-use agreements are vital. Striving for economic sustainability through member contributions and responsible resource management, cooperatives often prioritize environmental stewardship and community benefit. As autonomous, member-controlled corporations, they pool resources to meet mutual needs, ensuring democratic action and agreement even when engaging with local communities and businesses outside the cooperative.

- Mutual Benefit

In land cooperatives, collective ownership coexists with the members’ rights to use specific portions of the property or shared facilities as defined by cooperative rules and agreements, often linked to housing, agriculture, or other shared purposes. Sometimes structured as nonprofits or mutual-benefit entities, these cooperatives reinvest any surplus into the organization itself or it flows to members as benefit or profit. By collaborating across many aspects of members’ daily lives, cooperatives enhance needed services, strengthen local economies, and address social and community needs effectively.

- Membership

Cooperative membership is often inclusive, welcoming all who can use its services and are willing to accept membership responsibilities. This membership typically involves participating in decisions and attending meetings, following cooperative rules and bylaws, adhering to land-use agreements, potentially contributing labor or expertise, and contributing to economic sustainability via fees and responsible resource use. Members contribute to and democratically control the cooperative’s finances, a portion of which is usually shared. Instead of individual ownership, members hold shares granting them usage rights to specific areas for housing, farming, or community spaces, as governed by cooperative rules. Collective land use and management decision-making empowers members to shape their environment and promotes shared stewardship.

The Farmland Commons

The Farmland Commons model centers productive and regenerative land stewardship secured by community-centered nonprofit ownership for public benefit. This ensures not just the protection of natural resources and productivity of working farms but also addresses crucial aspects of land access and secure tenure for farmers. Unlike conservation easements that primarily focus on environmental protection through acquiring and permanently prohibiting certain rights that could degrade, extract, and commoditize the land’s natural attributes, a Farmland Commons actively owns land and secures tenure for regenerative farmers and prioritizes sustainable production. By adopting a nonprofit organizational structure, a Farmland Commons can leverage benefits such as the ability to secure grants and philanthropic funding, alongside accepting real estate donations, all while ensuring that the control, decision-making processes, and overall vision remain rooted within the local community.

- Ownership

The Farmland Commons takes privately held land and moves it into community-centered nonprofit ownership for public benefit. Much like land trusts that have successfully been transitioning land into and holding land in nonprofit ownership for public benefit for the last 120 years, the Farmland Commons uses nonprofit status to de-commodify the land. The Farmland Commons roots governance and operational structures into the local community through the collaborative structure of limited scope 501(c)(25) or 501(c)(2) nonprofit, land-holding affiliate entities. The nonprofits hold the land and all administrative roles therein, while the farmers or farmer enterprise lease the land from the nonprofit at an affordable rate and focus their efforts on regenerative farming. This nonprofit framework also offers long-term stability and oversight from regulatory bodies like the state attorney general and the IRS, safeguarding the land and other assets and ensuring the enduring nature of the Farmland Commons even in the face of organizational changes.

- Governance

The Farmland Commons are created by forming a land-holding entity through the establishment of an IRS-designated 501(c)(25) nonprofit, which is formed when three to 35 501(c)(3) nonprofits work together on a shared goal. A board is created for the 501(c)(25) that is made up of members of the parent 501(c)(3) organizations. These nonprofits can be national, regional, or local, but a focus is put on organizations that have community roots. Having a mix of local and national representation can greatly benefit the network by extending support and resources. The 501(c)(25) itself is a limited-scope entity that exists exclusively to hold title to acquired real estate, and manage and convey leases of this real estate to the farm.

The assembled board from the parent nonprofits determines the lease terms to the farmers or farm enterprise. The Farmers Land Trust advocates for affordability and equity by establishing a 99-year lease agreement. The board of the umbrella 501(c)(25) can harness its position to take in lease revenue and pursue tax-deductible, philanthropic funding acquired through the connections and partnerships held by the 501(c)(3) parent organizations. The leaseholders are valued not only for their skilled labor and land stewardship but also for their organizational insight, and they are automatically awarded a seat on the board.

The 501(c)(25) cannot raise money for or engage in activities beyond this specialized scope and narrowly focused mission, serving primarily as property-holding organizations. The 501(c)(25)’s activities are limited to acquiring, holding, stewarding, and leasing real estate. As an IRS-designated 501(c)(25), generated profits are reinvested into the missions and operations of the organization. The Farmland Commons model specifically reinvests all profits into agricultural infrastructure, land stewardship, and the real estate carrying costs for the real estate it holds ownership of. The 501(c)(25) is governed and led by a board of directors and does not have member control. The voting, decision-making, and controls are all established within the bylaws and founding documents.

- Mutual Benefit

Similarly, sprouting from a community holding a shared vision for the land, Farmland Commons are community-centered, nonprofit-held lands that have public benefits. The guiding force behind these shared benefits centers on the well-being and productivity of a farmer, farm collective, or farming family that uses the farmland to produce foodstuffs and other agricultural products in a way that supports the health of the landscape and community. The mutual benefits of food production, carbon sequestration, soil health, and ecological health all rely on community-supported farm viability and farmer security.

The leaseholders are valued not only for their skilled labor and land stewardship but also for their organizational insight, and they are automatically awarded a seat on the board.

- Membership

Membership within a Farmland Commons model encompasses several key elements, but most importantly, shared ownership does not directly correlate with shared use, individual benefits, or profits. Access to land is a central component, provided specifically to farmer members with secure tenure and autonomy, allowing them to cultivate the land with stability. Stewardship responsibilities are typically integrated into the farmer roles, expecting farmer members to manage the land according to sustainable practices outlined in the commons agreements, fostering a collective commitment to the long-term health of the farmland.

While structured differently than traditional cooperatives with direct voting rights, participation in government often involves nonprofit and community members having advisory roles or representation in decision-making processes concerning land use and management policies established by the commons board. Membership of the community is through these means as opposed to having direct access to the use of the land, profits, or benefits from the land, which is provided directly and exclusively to the farmers.

Hope Grows on Community-Held Lands

In embracing the seven principles of Land Cooperatives and the community-ownership structure of the Farmland Commons, we cultivate more than just the soil; we nurture the potential of a healthier future. These decentralized ownership models empower communities to view the care and well-being of their beloved landscapes, farmers, and shared resources as the key to community prosperity. By fostering shared responsibility, promoting ecological practices, and prioritizing equitable access, land cooperatives and the Farmland Commons sow the seeds for greater food security, stronger local economies, and a deeper connection between people and the land that sustains them.

fostering a collective commitment to the long-term health of the farmland.

In a world grappling with widening inequalities and the urgent need for ecological regeneration, the Farmland Commons and land cooperatives offer a compelling vision of land as a shared inheritance—decentralized, held for community benefit, and managed not for individual gain but for the enduring prosperity of both people and planet.